Deakin and his Bicycle

Professor Judith Brett is writing a biography of Alfred Deakin and here explores his discovery of the bicycle and related brushes with the law.

Not until Tony Abbott has Australia had a prime minister so dedicated to vigorous exercise as was Alfred Deakin. Deakin liked to begin his day with something to open up the lungs and get the blood racing – chopping wood, skipping backwards, playing hockey with the children, if he was in the country cutting scrub or a bracing horse ride, if at the seaside he would bathe. When he travelled, he took his skipping rope so that he could exercise on board ship, or in the hotel yard. His youngest daughter Vera remembered that when the family went with him to London in 1900 for the passing of Australia’s Constitution Bill through the British Parliament, they stayed in a small hotel with a flat roof so he could skip before going off to his long days and nights of meetings, luncheons, dinners and banquets.

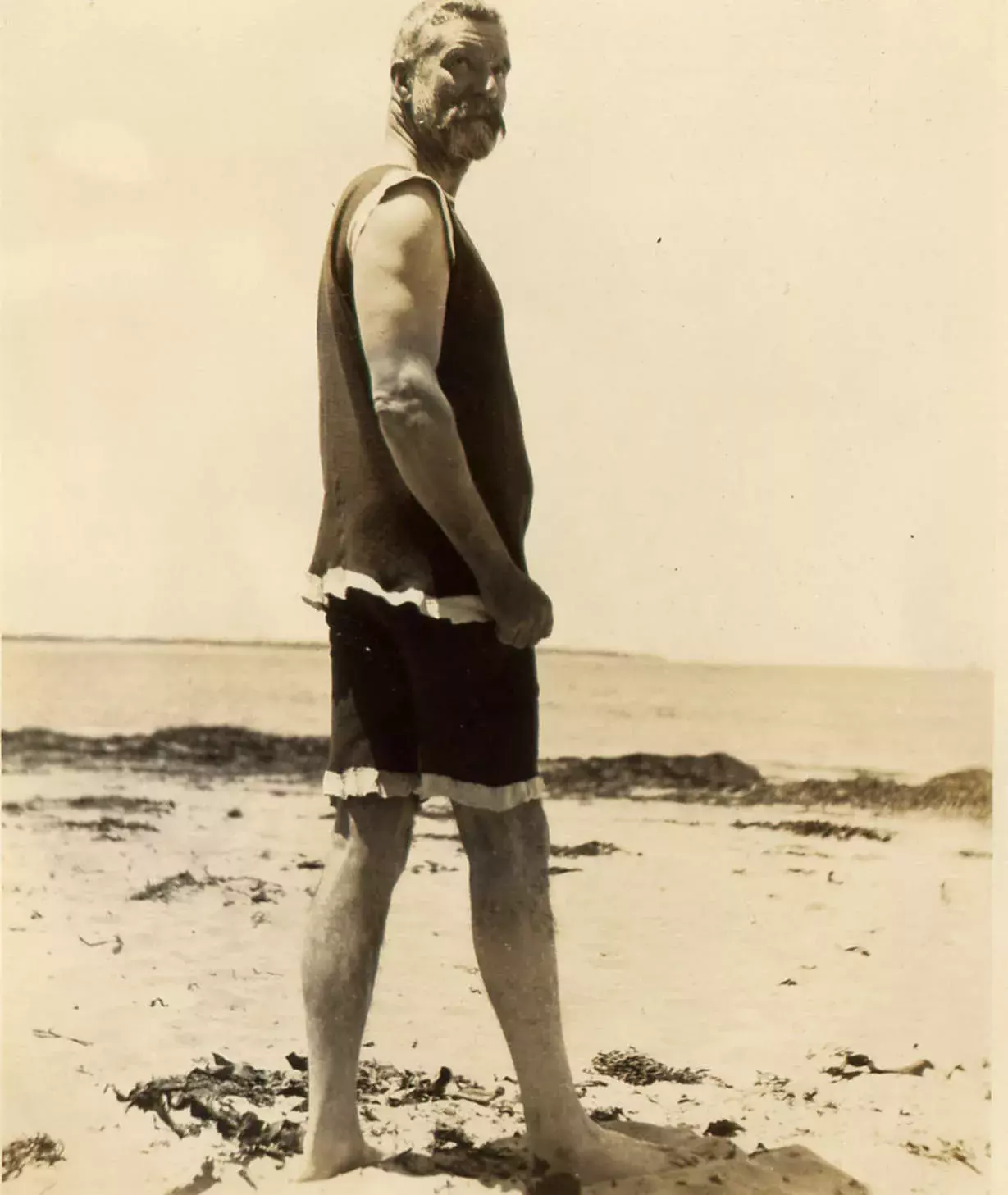

Alfred Deakin at Point Lonsdale, 1910.

Photo: ADPML/Deakin University

When Deakin first became a member of Parliament at the very young age of twenty-two he would walk from the house where he still lived with his parents, in Adam Street South Yarra, or catch the tram as he did when he and his wife Pattie lived in their own house a few blocks away in Walsh Street South Yarra. Although his father had been in the coaching business, first as an owner operator with his brother-in-law and later working for Cobb & Co, Deakin never kept carriage. Sometimes after a late night sitting he would take a cab. And after the cycling craze hit Melbourne in the mid-1890s, he would cycle.

Bicycles in various forms had been around since the 1860s, but the first machines were dangerous and difficult to ride, and it was mainly athletic young men who took them up. In the early 1890s the ‘safety bicycle’ replaced the high-wheeled penny farthing, and modern cycling was born. The safety bicycle was very similar to the modern bike, with pneumatic tyres, a diamond shaped frame, and chain driven wheels with the pedals in the middle of the bike rather than attached to the front wheel. Cycling was now much safer and easier, and moved from a specialist pastime to a popular form of transport and recreation. In 1894, there were 8,000 cyclists in Melbourne, and in 1895 thirty-eight businesses making, importing and repairing bicycles. The new safety bicycles were not only safer and more comfortable than their predecessors, they were also cheaper. And they were a good deal cheaper than buying, feeding and stabling a horse.

On 21 August 1895, having just turned 39, Deakin took his first of six bicycle lessons. He was an immediate enthusiast and spent the next weekend practising in the quiet roads and paddocks at Woodend. The wide and relatively flat streets of Melbourne were ideally suited to cycling, and most days he went for a ride, at first just round South Yarra where he lived, cycling to his childhood home to visit his mother and sister, or around Albert Park Lake, but he was soon venturing further afield – to the Brighton cemetery where his father William was buried, or round the bay as far as Red Bluff.

He bought his bicycle from Edward Beauchamps’ Prahran Cycle Arcade in Chapel Street, who advertised that ‘the hon Alfred Deakin is one of the gentlemen riding my bicycle.’ Beauchamps’ roadsters, made on the premises using imported bearings and tyres, sold for 21 pounds, and he also had a bicycle hospital to repair fractures and mend tyres. The hustle of his premises, reported the Weekly Times, ‘conveys the idea that cycling as a pastime, a health practice and a convenience for travelling is establishing itself firmly in Melbourne.’

A couple of months later Deakin bought a bicycle from Beauchamps for his eldest daughter, Ivy, who was twelve, and they rode often together. On Deakin’s encouragement his sister Katherine, then in her mid-forties, was soon cycling too, and his other two daughters when they were old enough, but not his wife Pattie. The drop frame and wheel and chain guards enabled women to ride without their skirts tangling in the chain and spokes; and some even wore divided skirts. The bicycle gave women unprecedented mobility and independence, and was regarded with some trepidation by conservative society. Deakin and Pattie were generally protective of their three daughters, who lived sheltered, home-centred lives, but he had no qualms about them taking up cycling. The family holidayed at Point Lonsdale, and in December 1895 he and Ivy rode their bicyles to Port Melbourne to put them on the steamer which would take them down the bay to Queenscliff from where they would ride to Point Lonsdale. For the six months or so after he started cycling, Deakin recorded every ride in his diary, but gradually the novelty wore off and fewer rides were mentioned.

In 1895 Deakin had the time to take up a new enthusiasm. In the late 1880s, the hey-day of Marvellous Melbourne, he had been the Chief Secretary in a coalition government, feted for his youth and his oratory. But since the financial crises and bank crashes of the early 1890s he had lost faith in Victorian politics and was only staying in Parliament in the hope of assisting the cause of federation. On the back bench, refusing all offers of ministerial positions, he had returned to the bar to supplement his members’ allowance of 400 pound a year. This was a princely sum for a worker but not enough to maintain a middle class household of a wife, three daughters and two servants.

The cause of federation had been progressing in fits and starts but a conference at Corowa on the Murray in 1893 had come up with a plan. Voters in each colony would elect representatives to a convention which would determine a Federal Constitution Bill which would then be submitted to the people. Deakin was elected as one of Victoria’s representatives to the convention, the first sitting of which was held in Adelaide at the end of March 1897. Deakin took his bicycle with him on the train. He was staying at the sea side resort of Largs Bay so he could begin each day with a sea bath, and then cycle the nine miles into the SA Parliament where the convention was sitting.

The first Commonwealth Parliament met in Melbourne, so when Deakin became a Commonwealth Minister, and then Prime Minister, he could still ride his bicycle to and from Parliament House. In 1905, when he became Prime Minister for the second time, he bought a new bicycle. And twice the following year, his riding drew the attention of a watchful policeman. In February a policeman on point duty stopped Deakin for riding his bicycle on the wrong side of the road at the corner of Flinders and Swanston Street. The constable applied for a summons which the inspecting superintendent refused to grant and the incident would have disappeared from view, except that it was raised during a Police Commission into the regulation of traffic as an example of discrimination amongst offenders. The Cabmen’s Union complained that a cab driver who was driving the Lady Mayoress rapidly down the wrong side of the road to try to catch the Warnambool train was charged, whereas the Prime Minister was let off with a warning. Was it only prime ministers who were allowed to break the regulations?

Melbourne’s Punch published a satirical poem on the incident. When confronted with the charge,

Then came a rush of rapid verse.

The proud defendant, Alfred Deakin,

At lightning speed had started speaking.

Deakin was renowned for his oratory. In full flight he spoke at more than two hundred words a minute, but his political sympathies were not always obvious. The first ten years of the Commonwealth were unstable as the rapid growth in Labor’s electoral support unsettled the established opposing parties of Free Traders and Protectionists. For a time there were three equal parties in the Parliament, and each had a turn of governing. First Protectionist Deakin was Prime Minister, supported by Labor, then Labor formed a government with half-hearted support from Deakin, then Free Trader George Reid became Prime Minister with half-hearted support from Deakin, and finally in July 1905 Deakin became Prime Minister for a second time, again with Labor’s support. Through all these twists and turns, it was hard to know exactly where Deakin stood. Often it seemed he wasn’t too sure himself; and now he’d been caught by riding the wrong way down the road. The constable speaks, playing with right and left in the road rules to satirise Deakin’s political about turns:

"You're on the right, and

in the wrong," he said.

I saw myself—the picture made me blind—

Hauled up, and ignominiously fined.

Of sense of Orientation quite bereft.

I murmured: "He was right, and I'll be left."

How can I plead ? Nay, what are right and Wrong

To me, they never seem the same for long.

I am a bubble blown that way and this

To some ideal that I always miss.

In politics, the left becomes the right,

The right the left, within a single night;

A compass is not easy to obey

Which every morning points a different way.

As Prime Minister, he was just one of the crowd of cyclists riding to and from work each day, and in June of the same year he was among a dozen people charged in the District Court with riding on the footpath contrary to by law 103. The footpath in question was the section of Swan Street which runs through what is now Olympic Park, by the Yarra, on the route between Deakin’s home and Parliament, and the plain clothes policeman who had brought the charges said several women and children had been knocked over by cyclists on that footpath. Deakin did not appear, but a letter from him was read to the court. He admitted he was liable for the penalty, but he wrote, ‘I should like the court clearly to understand that I am not aware I was breaking any by-law. For more than five years I have walked or cycled through the park and along that part of the road several times every week, I have seen hundreds of cyclists in broad daylight using that path morning and evening as freely as they do the path on the other side of the rail… When I cycled I assumed that such uses are permitted.’ The magistrate accepted that Mr Deakin did not know that he was breaking any by-law, and fined him 2/6d with 2/6d costs.

Deakin’s second period as Prime Minister lasted until June 1908 when Labor withdrew its support for his government and Andrew Fisher became Prime Minister. Fisher thought that the Prime Minister needed more dignified means of transport than the tram, bicycle and shanks pony, and ordered the purchase of a Prime Minister’s car. Deakin himself never owned a motor car. Deakin did not see himself as a man of the people, he was too private and intellectual for that, but nor did he think of himself as deserving any special privileges because of his high office. Famously he refused all offers of a knighthood and many a morning could be found riding to work with other Melbournians.

Notes

1. Interview with Vera White (nee Deakin), NLA Oral history, TRC 4802

2. R.Hess, ‘A mania for bicycles: The Impact of Cycling on Australian Rules Football, Sporting Traditions, 14/2, May 1998; Sands & McDougall, 1895.

3. Weekly Times, 2/5/1896, p. 39.

4. Very frequent diary entries on cycling 21/8/1895 passim

5. Fiona Kinsey, ‘Australian Women Cyclists in the 1890s’ in Claire Simpson, ed,Scorchers, Ramblers and Rovers: Australasian Cycling Histories, Australian Studies in Sporting History, no 21, 2006.

6. Diary, March 1897.

7. Diary, 2/9/1905.

8. Ballarat Star, 19/1/1906, p. 6; Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 26/1/1906.

9. Express and Telegraph (Adelaide), 26/6/1906.

10. J. A. La Nauze, Alfred Deakin: A Biography, vol 1, p. 312-3.